Introduction

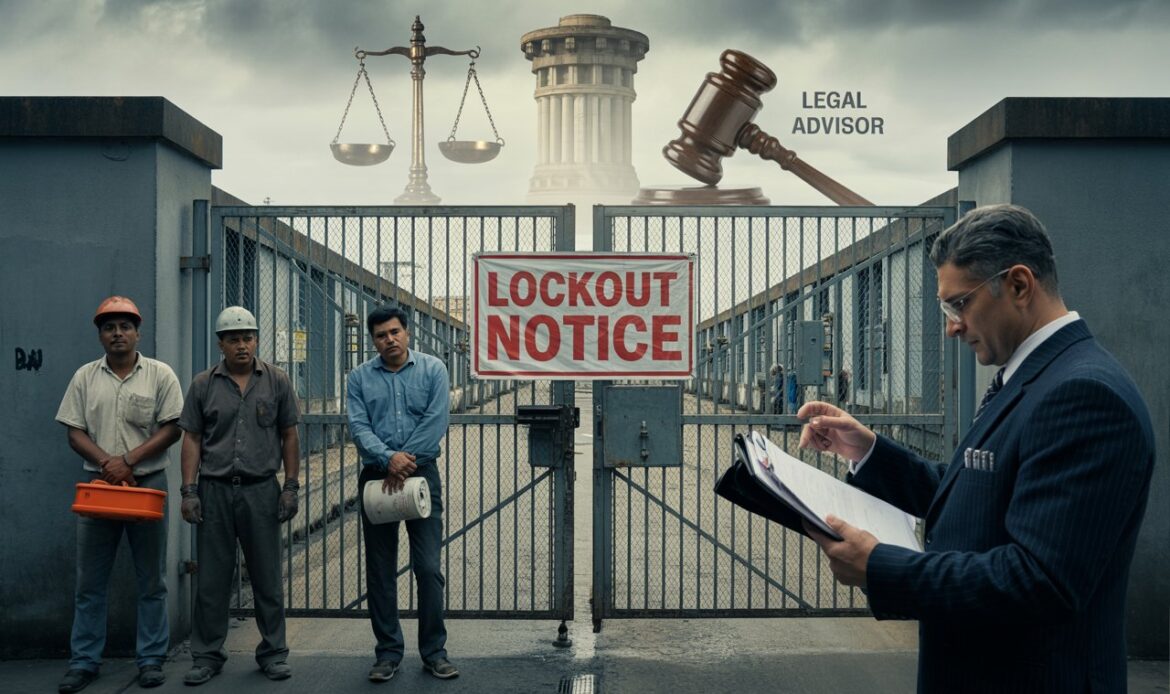

Just as a strike serves as a potent weapon for employees to enforce their industrial demands, a lockout represents a corresponding tool available to the employer. It is employed as a coercive measure to persuade employees to accept the employer’s viewpoint or demands. In essence, a lockout stands as parallel to a strike, reflecting the inherent power dynamics within industrial relations.

The framework surrounding lockouts in India is both intricate and stringent. The Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, places certain procedural and substantive limitations on their use, particularly in public utility services and during ongoing conciliation or adjudicatory proceedings. Failure to comply with these safeguards may render a lockout illegal or unjustified, with serious implications for the employer, including potential liability for back wages and penalties under the Act.

Definition of a Lockout

According to Webster’s Dictionary, ‘lock-out’ is the withholding of employment by an employer and the whole or partial closing of his business establishment to gain concessions from employees.

Section 2(l) of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, provides the statutory definition of “Lockout” as the closing of a place of employment, or the suspension of work, or the refusal by an employer to continue to employ any number of persons employed by him.

The definition of a lockout has three ingredients:

- temporary closing of a place of employment by the employer, or

- suspension of work by the employer, or

- refusal by an employer to continue to employ any number of persons employed by him.

It is crucial to understand that, similar to a strike, a lockout does not entail a severance of the employment relationship. Instead, the relationship is merely suspended temporarily. A lockout is neither an alteration to the prejudice of the conditions of service nor a discharge or punishment by dismissal or otherwise, as held in the case of Lakshmi Devi Sugar Mills Ltd. v Ram Sarup (1957).

In case of lockout, the workmen are asked by the employer to keep away from work, and, therefore, they are not under any obligation to present themselves for work. The legality and justification of a lockout are critical in determining the employer’s liability, particularly concerning the payment of wages during the lockout period. For instance, a lockout was deemed fully justified where a manager was violently attacked by staff members in the case of Karrietta Estate v Rajamanickam.

The liability of the employer in case of lock-out would depend on whether the lock-out was justified and legal, or not, and whether the provisions regarding lay-off compensation were applicable not applicable.

A lockout may sometimes be put in place not because of economic demands, but it may be resorted to as a security measure, as seen in the case of Lord Krishna Sugar Mills Ltd. v State of U.P. 1960-II LLJ 76. In this case, the textile mill was closed down by the employer with the object of teaching the workmen a lesson for the incident of assault on the general superintendent of the mill. It was resorted to as a measure of retaliation, and hence was classified as unjustified. The lock-out was also considered illegal since there was no prior notice. Therefore, the workmen were entitled to wages for the period of lock-out.

Prohibition of Lockouts

Similar to the prohibitions on strikes, the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 imposes restrictions on lockouts, particularly in public utility services and during certain proceedings.

1. Restrictions in Public Utility Services

Just as the strikes are prohibited in public utility services under Section 22(1), lockouts are similarly prohibited under Section 22(2) of the Act under analogous circumstances. No employer, carrying on any public utility service, shall lock out any of his workmen.

- without giving them notice of lock-out within six weeks before locking out; or

- within fourteen days of giving such notice; or

- before the expiry date of lock-out specified in any such notice as aforesaid; or

- during the pendency of any conciliation proceedings before a conciliation officer and seven days after the conclusion of such proceedings.

The notice of the lock-out under Section 22(3) shall not be necessary where there is already a strike in existence, but the employer will have to send intimation of such lock-out on the day on which it is to be declared, to such authority as may be specified by the appropriate Government.

2. General Prohibition of Lockouts

Section 23 of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, acts as a general prohibition on lockouts. As per this section, a lockout cannot be put into place when:

- There is a pendency of conciliation proceedings before a Board and seven days after the conclusion of such proceedings.

- The proceedings are pending before a Labour Court, Tribunal or National Tribunal, and two months after the conclusion of such proceedings.

- The arbitration proceedings are pending before an arbitrator, and two months after the conclusion of such proceedings, where a notification has been issued under sub-section (3A) of section 10A; or

- A settlement or award is in operation, in respect of any of the matters covered by the settlement or award.

3. Illegal Lockouts

According to Section 24 of the Act, a lockout is deemed illegal if it is commenced or declared in contravention of Section 22 or Section 23, or in contravention of an order made under Section 10(3) (prohibiting continuance of lockout) or Section 10A(4A) (prohibiting continuance during arbitration). Just as Section 26(1) penalizes employees for illegal strikes, Section 26(2) penalizes an employer for illegal lockouts. A lockout commenced within seven days of conciliation proceedings would be illegal if it results from an already commenced illegal strike (General Navigation & Railway Co. Ltd. v Workmen AIR 1960 SC 219).

Case Analysis

SHRI RAMCHANDRA SPINNING MILLS v STATE OF MADRAS (AIR 1956 Mad 241)

In the case of Shri Ramchandra Spinning Mills v. State of Madras, the core issue revolved around the mill’s closure and whether it could be constituted as a lockout or not. The mill was facing an ongoing enquiry regarding dearness allowance rates when the government referred the broader wage structure issue to an adjudicator. Subsequently, the mill closed from July 1947 to March 1948. The State of Madras, viewing the closure as a lockout, took action against the mill. The mill contested this, arguing the closure was due to financial reasons and not an industrial dispute.

The Madras High Court laid down some tests to determine whether suspension of work by the employer is a lockout or not. The court observed that whatever be the circumstances in which an employer finds himself placed, if an employer closes the place of employment or suspends work on his premises, a “lockout” would come into existence.

Lockout is the antithesis of strike. The lockout acts as the corresponding weapon in the armoury of the employer. If an employer shuts down his place of business as a means of reprisal or as an instrument of coercion or as a mode of exerting pressure on the employees, or generally speaking, when his act is what may be called an act of belligerency, there would be a lockout. On the other hand, if the employer shuts down his work because he cannot, for instance, get the raw materials or the power necessary to carry on his undertaking, or because he was unable to sell the goods he has made, or because his credit was exhausted, that would not be considered a lockout.

In the present case, the court held that the mill’s closure was a bona fide business decision due to financial losses and not an illegal lockout. The court found that the government’s declaration of an illegal lockout was based on mistaken facts and deemed it null and void.

Lockout v. Closure

The terms ‘lockout’ and ‘closure’ both seem to be related and involve a cessation of work; however, they differ significantly in their nature and duration. Lockout is defined under Section 2(l) of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 as a “temporary closure of the place of employment, or suspension of work, or refusal by the employer to continue employing any number of workmen”, while closure is defined under Section 2 (cc) as the “permanent shutting down of a place of employment or part thereof by the employer”. In the cases where the suspension of work is ordered, it would constitute a lock-out.

Lockout is a weapon of coercion in the hands of the employer, while closure is generally for trade reasons. The closure produces legal effects on the rights of workers under the scheme of the Act, as compared to lockout, which is a legal means under the prevailing conditions in the hands of the employers to be used against the employees.

A closure requires a 60-day notice to the appropriate government before closing an undertaking employing more than 50 workmen as per Section 25FFA, while a prior government permission, in case of industrial establishments employing 100 or more workmen. While in the case of lockout, a notice must be given at least 14 days in advance per Section 22.

In the case of a Closure, Workmen are entitled to compensation, subject to eligibility under Section 25F or 25N, while in the case of a Lockout, no automatic compensation is provided unless it is declared illegal or unjustified by the appropriate authority.

In the case of Express Newspaper Ltd. v Their Workmen (1962) 2 LLJ 227, the Supreme Court distinguished between lockout and closure as:

- In closure, there is severance of employment relationship, while in lockout, there is no severance of such relationship, but there is only suspension.

- Lockout is caused by the existence or apprehension of an industrial dispute. A closure need not be in consequence of an industrial dispute.

- A lockout is a tactic in bargaining. While the closure is shutting down employment and thereby ending bargaining.

Thus, in closure, there is no intention on the part of the employer to continue the business, whereas in lockout, the employer always has the intention to continue the business if his demands are accepted by the workmen. The employer does not have a fundamental right to lockout, even though he has one to closure. Thus, an employer might be guilty of unfair labour practice in case of lockout, but not in closure.

Conclusion

The lockout, as defined and regulated by the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, serves as the employer’s counter-weapon to a strike, enabling them to exert pressure on employees during industrial disputes. While it involves the temporary cessation of work or refusal to employ, it fundamentally differs from a permanent closure of business. The Act imposes stringent prohibitions on lockouts, particularly in public utility services and during the pendency of conciliation, adjudication, or arbitration proceedings, reflecting the restrictions placed on strikes.

The implications of a lockout, including the entitlement to wages and the employer’s potential liability, depend critically on its legality and justification, which are determined by the adherence to statutory provisions and the intent of the employer. The distinction between a bona fide closure for genuine business reasons and a lockout as a coercive tactic is necessary, with courts examining the employer’s true intention. This intricate legal framework underscores the Act’s objective to regulate industrial relations, ensuring that both employers and employees exercise their respective rights and weapons within a defined legal boundary, thereby striving to maintain industrial peace and harmony.

About Us

Corrida Legal is a boutique corporate & employment law firm serving as a strategic partner to businesses by helping them navigate transactions, fundraising-investor readiness, operational contracts, workforce management, data privacy, and disputes. The firm provides specialized and end-to-end corporate & employment law solutions, thereby eliminating the need for multiple law firm engagements. We are actively working on transactional drafting & advisory, operational & employment-related contracts, POSH, HR & data privacy-related compliances and audits, India-entry strategy & incorporation, statutory and labour law-related licenses, and registrations, and we defend our clients before all Indian courts to ensure seamless operations.

We keep our client’s future-ready by ensuring compliance with the upcoming Indian Labour codes on Wages, Industrial Relations, Social Security, Occupational Safety, Health, and Working Conditions – and the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023. With offices across India including Gurgaon, Mumbai and Delhi coupled with global partnerships with international law firms in Dubai, Singapore, the United Kingdom, and the USA, we are the preferred law firm for India entry and international business setups. Reach out to us on LinkedIn or contact us at contact@corridalegal.com/+91-9211410147 in case you require any legal assistance. Visit our publications page for detailed articles on contemporary legal issues and updates.