Introduction

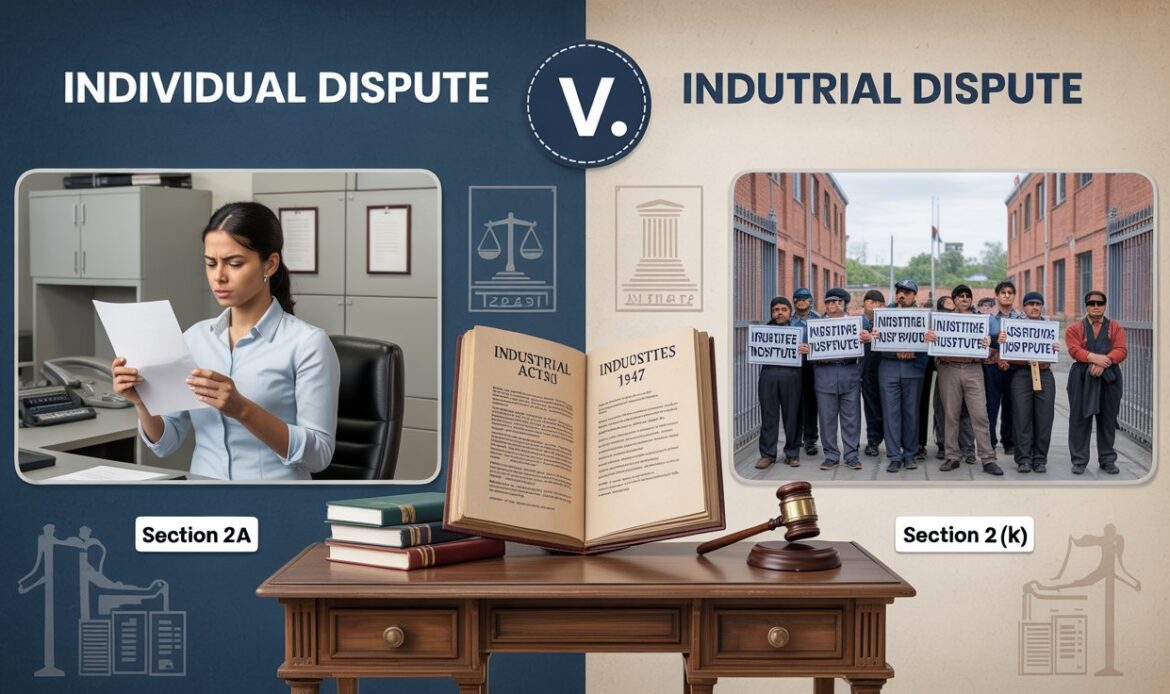

In India, whenever an industrial dispute takes place, the emphasis is often placed on collective bargaining powers and support of Trade Unions. However, among such prevalent methods of collective bargaining or collective espousal, often the plight of an individual workman goes overshadowed. The Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 (hereinafter, ‘the Act’) was initially conceived to address collective disputes between employers and ‘workmen’ and left an individual employee in a cornered position, frequently lacking the requisite collective support to invoke the Act’s protective mechanism.

However, the labour laws have evolved to address this concern. The Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, was amended in 1965, and its foundation was the insertion of Section 2A. Subsequent amendment was made to Section 2A in 2010, which significantly empowered individual workmen by granting them direct access to adjudication for specific types of disputes. This article will examine key statutory developments along with landmark judicial pronouncements to decode the legal framework that now governs the transformation of an individual grievance into a recognized industrial dispute, ultimately ensuring greater access to justice and a more equitable balance in employer-employee dynamics.

Evolution of Individual Disputes

The question of whether a single workman, aggrieved by an employer’s action, could raise an industrial dispute was always a point of significant judicial opinion. Broadly, three different views prevailed:

- A dispute which concerns only the rights of an individual worker cannot be held to be an industrial dispute.

- A dispute between an employer and a single employee can be an industrial dispute, and

- A dispute between an employer and a single employee cannot per se be an industrial dispute, but it may become one if it is taken up by the union or a number of workmen.

Before the insertion of Section 2A, the Act used the plural “workmen,” which led to the conclusion that an individual dispute could not, by itself, be an industrial dispute, but it could become one if it was taken up by the Trade Union or a group of workmen. The provisions of the Act lead to the conclusion that its applicability to an individual dispute as opposed to dispute raised by a group of workmen is excluded unless it acquires the characteristics of an industrial dispute, viz. the verdict or decision of a considerable section of them make common cause (Newspaper Ltd. v. State Industrial, U.P. AIR 1957 SC 304).

Thus, a dispute regarding a single workman can become an industrial dispute only if it is espoused by a group of workmen in the establishment. Only a collective dispute could constitute an industrial dispute, but a collective dispute does not mean that the dispute must either be sponsored by a registered union or that the workman in the particular establishment should be parties to the dispute.

The only condition for an individual dispute to turn into an industrial dispute, was the necessity of community of interest which must exist at the date of reference, wherein the concerned workman need not be a member of the Union as held in the case of Western India Match Co. Ltd. v. Western India Match Co. Workers’ Union (1970) 1 SCC 225.

Once a dispute was validly referred, it would not cease to be an industrial dispute merely because workmen subsequently withdrew their support as held in the case of Working Journalists of Hindu, Madras v. The Hindu, Madras (1960).

Similarly, where an industrial dispute existed at the time of making order of reference, the dispute does not cease to be so merely because the dispute was related to only one employee and the Union which raised the dispute later changed its stance regarding that particular employee, as held in case of Binny Ltd. v. Their Workmen AIR 1972 SC 1975.

The Act provided no specific indication as to the minimum number of workers required to espouse an individual dispute for it to transform into an industrial dispute. Not all the workmen or a majority of employees of the establishment concerned need to support and sponsor the individual dispute. However, there must be a substantial or appreciable number of workmen of the class of aggrieved workman as held in the case of Mrs. B.R. Patel v. Union of India (1970) I LLJ 558 (AP).

In the case of Workmen of Indian Express Newspapers Ltd. v. Management of Express Newspapers (AIR 1970 SC 737), a dispute relating to the dismissal of a working journalist of Indian Express was espoused by the Delhi Union of Journalists, which was an outside union. About 25 out of 30 of the working journalists of the Indian Express were members of that union. But there was no Union of the workmen of Indian Express. It was held that the Delhi Union of Journalists could be said to have a representative character qua the working journalists employed in Indian Express, and the dispute was thus transformed into an industrial dispute.

Section 2A: Legislative Intervention for Individual Grievances

The judicial inclination towards the view that individual disputes could not inherently be ‘industrial disputes’ under the Act often left individual workmen without effective legal recourse. A workman, if not a member of a recognized trade union, might find the union reluctant to espouse their cause, leaving them remediless.

Cases came to light where the recognized union by devious means compelled the workman to be its member before it would espouse their causes. Thus, a workman who was discharged, dismissed, retrenched, or whose services were otherwise terminated was put to great hardship when he could not find support by a union or an appreciable number of workmen to take up his cause.

This trade union tyranny was taken note of by the Legislature and Section 2A was introduced in the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947.

In 1965, The Industrial Disputes (Amendment) Act, 1965 inserted Section 2A, which reads: “Where any employer discharges, dismisses, retrenches or otherwise terminates the services of an individual workman, any dispute or difference between that workman and his employer connected with, or arising out of, such discharge, dismissal, retrenchment or termination shall be deemed to be an industrial dispute notwithstanding that no other workman nor any union of workmen is a party to the dispute.”

Section 2A came into force on 1-12-1965. Section 2A can be treated as an explanation to Section 2(k). It was expected that an individual dispute, though not sponsored by other workmen or espoused by union, would be deemed to be an industrial dispute if it covers the matters mentioned in Section 2A. But whether a particular dispute amounts to an industrial dispute had to be ascertained after applying the principle laid down in Section 2(k). So far as the subject matter of dispute was concerned, Section 2A does not bring about any change. The provisions of Section 2(k) alone determine that question.

Limited Application of Original Section 2A:

The application of the original Section 2A was limited. The Section does not declare all individual disputes to be industrial disputes, but covers only cases of discharge, dismissal, retrenchment, or other termination of service. If the dispute was connected with other matters (e.g., conditions of labour, etc.), it would have to satisfy the test laid down in judicial precedents. If the management demotes a workman, or withholds his increment, or reduces his rank in the seniority list, or accords him other similar kind of adverse treatment, any industrial dispute in such a case will have to be supported by a substantial number of workmen.

Industrial Disputes (Amendment) Act, 2010

In Section 2A, two sub-sections (2) and (3) were added by the Industrial Disputes (Amendment) Act, 2010, w.e.f. 15th September 2010. Section 2A of the principal Act was numbered as sub-section (1) thereof:

“(2) Notwithstanding anything contained in Sec. 10, any workman as is specified in sub-sec. (1) may, make an application to the Labour Court or Tribunal for adjudication of the dispute referred to therein after the expiry of three months from the date he has made the application to the Conciliation Officer of the appropriate Government for conciliation of the dispute, and in receipt of such application the Labour Court or Tribunal shall have powers and jurisdiction to adjudicate upon the dispute, as if it were a dispute referred to it by the appropriate Government by the provisions of this Act and all the provisions of this Act shall apply about such adjudication as they apply about an industrial dispute referred to it by the appropriate Government.

(3) The application referred to in sub-sec. (2) shall be made to the Labour Court or Tribunal before the expiry of three years from the date of discharge, dismissal, retrenchment, or otherwise termination of service as specified in sub-section. (1).”

Effect of 2010 Amendments:

Before the 2010 amendments, normally only collective disputes or disputes raised by a group of workmen were taken up as industrial disputes. An individual workman could raise a dispute only if it fell under the exceptional cases listed in Section 2A, such as cases of dismissal/discharge/retrenchment/termination. For non-termination issues (like promotion/ transfer/ punishments not amounting to termination) individual workman couldn’t raise a dispute if no other workmen are supporting his case.

However, after the 2010 amendment, any person who is a workman employed in an industry could raise an industrial dispute (via use of ADR procedures like Conciliation). Any workman specified in sub-section (1) (i.e., those whose services have been discharged, dismissed, retrenched, or otherwise terminated) can directly apply to the Labour Court or Tribunal for adjudication. This direct access was permissible after three months from the date the workman applied to the Conciliation Officer for conciliation of the dispute. The Labour Court or Tribunal then possesses the power and jurisdiction to adjudicate the dispute as if it were a reference made by the appropriate Government under Section 10 of the Act. A limitation period of three years from the date of termination was prescribed for such applications.

This amendment significantly empowered individual workmen in termination-related disputes by providing them with a direct avenue for redressal, bypassing the traditional requirement of union espousal or collective support.

Case Analysis

J.H. Jadhav v Forbes Gokak Ltd. (2005) 3 SCC 202:

In the case of J.H. Jadhav v Forbes Gokak Ltd. (2005) 3 SCC 202, the appellant was employed by the respondents. He claimed promotion as a clerk. When the promotion was not granted, he alleged and raised an industrial dispute. It was contended by the respondents that the individual dispute raised by the appellant was not an industrial dispute within the meaning of Section 2(k) of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, as the workman was not being supported by a substantial number of workmen belonging to the majority union. In this case, the appellant was a member of a different union, namely, Gokak Mills Staff Union. The objection was that the Gokak Mills Staff Union was not the majority union.

It was held that, for a dispute relating to a single workman to be addressed as an industrial dispute, it must either be espoused by the union of workmen or by several workmen. Further, the dispute should be connected with the employment or non-employment of a workman. In this case, the individual dispute was espoused by the Union, and the appellant employee raised the dispute as to promotion.

The objection in this case was that the union espousing the cause of the workman was not the majority union, but this objection was rightly rejected by the Tribunal and was also accepted by the High Court. The Supreme Court held that “the union” includes “minority unions” and “outside unions.” The term “union” merely indicates the union to which the employee belongs, even though it may be a union of a minority of employees in the establishment, or the union of another establishment belonging to the same industry.

The Supreme Court cited its earlier decision in Workmen v Dharampal Premachand (Saugandhi), where it was held that for Section 2(k), it must be shown that:

(1) The dispute was connected with the employment or non-employment of a workman.

(2) The dispute between a single workman and his employer was sponsored or espoused by the union of workmen or by several workmen. The phrase “the union” merely indicates the union to which the employee belongs, even though it may be a union of a minority of the workmen.

(3) The establishment had no union of its own, and some of the employees had joined the union of another establishment belonging to the union of same industry. In such a case, it would be open to that union to take up the cause of the workmen if it was sufficiently representative of those workmen, even though such union was not exclusively of the workmen working in the establishment concerned.

The Court also noted that no particular form is prescribed for espousal, though a resolution is common. Proof of support can be established through other means, depending on the facts of each case.

Conclusion

The journey from an individual dispute to an industrial dispute in India reflects a progressive evolution aimed at ensuring justice for individual workmen within a framework which was historically centered on collective bargaining. The judicial decisions initially emphasized collective espousal, which required the support of a union or a substantial number of workmen and often would lead to underscore the individual nature of industrial disputes. However, with the recognition of practical difficulties faced by individual workmen, particularly in cases of termination, Section 2A was inserted in the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947.

The original Section 2A deemed the individual termination dispute as an industrial dispute; however, it lacked applicability. The subsequent amendment made by the means of Industrial Disputes (Amendment) Act, 2010, strengthened the applicability of Section 2A by granting individual workmen direct access to Labour Courts or Tribunals for adjudication of their matters, subject to a prior conciliation attempt and a prescribed limitation period. Both of these amendments not only provided access to the dispute resolution mechanism but also acknowledged the inherent power imbalance between an employer and an individual employee. While the unions continue to play a vital role in representing collective interests, the law now empowers individual workmen to challenge unfair practices independently, thus reaffirming the fundamental principle of equality before the law. Such an evolving legal landscape has ensured that individual grievances, especially concerning important aspects of employment like termination, are not overshadowed in the broader collective framework but are provided due legal recognition and recourse.

About Us

Corrida Legal is a boutique corporate & employment law firm serving as a strategic partner to businesses by helping them navigate transactions, fundraising-investor readiness, operational contracts, workforce management, data privacy, and disputes. The firm provides specialized and end-to-end corporate & employment law solutions, thereby eliminating the need for multiple law firm engagements. We are actively working on transactional drafting & advisory, operational & employment-related contracts, POSH, HR & data privacy-related compliances and audits, India-entry strategy & incorporation, statutory and labour law-related licenses, and registrations, and we defend our clients before all Indian courts to ensure seamless operations.

We keep our client’s future-ready by ensuring compliance with the upcoming Indian Labour codes on Wages, Industrial Relations, Social Security, Occupational Safety, Health, and Working Conditions – and the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023. With offices across India including Gurgaon, Mumbai and Delhi coupled with global partnerships with international law firms in Dubai, Singapore, the United Kingdom, and the USA, we are the preferred law firm for India entry and international business setups. Reach out to us on LinkedIn or contact us at contact@corridalegal.com/+91-9211410147 in case you require any legal assistance. Visit our publications page for detailed articles on contemporary legal issues and updates.